My work is a sculptural realization of lived experience, thus responsible for its’ chaotic path. I have times working in chocolate, cotton candy, or found plastic and everything in between. Work for me is about the process, the manipulation of a given material, and treating these materials as temporary guests in my hands. The drive for me has always been the sacred found object, an object with its own history given to me to mold into another narrative. Eventually, we realize that our own body and self is also found object, given briefly so we too can write our own story.

As the son of an obstetrician and the town coroner, Shanabrook spent his childhood working at a chocolate factory and building robots in the basement of his house in rural Ohio. Now living between New York and Moscow after years in The Netherlands, Shanabrook funnels his life’s influences into a unique vision of surreal beauty formed on the threshold of entropy and disaster. His vision comes very near to the edge where one usually turns back. Shanabrook gives a new and often disturbing meaning to substances and forms otherwise associated with comfort, happiness, and banality – chocolate, plastic toys, and candies. Shanabrook was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1965. He received a BFA from Syracuse University and studied in Florence, Italy. He has participated in residencies at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and De Atelier in The Netherlands. Shanabrook has exhibited throughout the world in numerous solo and group exhibitions, including Drawing Center / New York, Swiss Institute / New York, and Moscow Biennale. The artist received numerous American and European grants, as well as public commissions. His works is part of public and private collections in the USA, Europe, Russia, and Australia, including Damien Hirst’s “murder me” collection and David Walsh’s controversial MONA museum. From 2010 Stephen j Shanabrook also collaborates on several projects with Veronika Georgieva. Together they created an advertising campaign for renowned fashion label Comme des Garçons for Spring/Summer 2010. The artists also collaborated with Saatchi and Saatchi advertising agency to create an ad campaign for the 25th anniversary of Reporters Without Borders in 2010, which included TV commercial. The campaign was shortlisted for Lion Award at Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival.

CONCEPTS

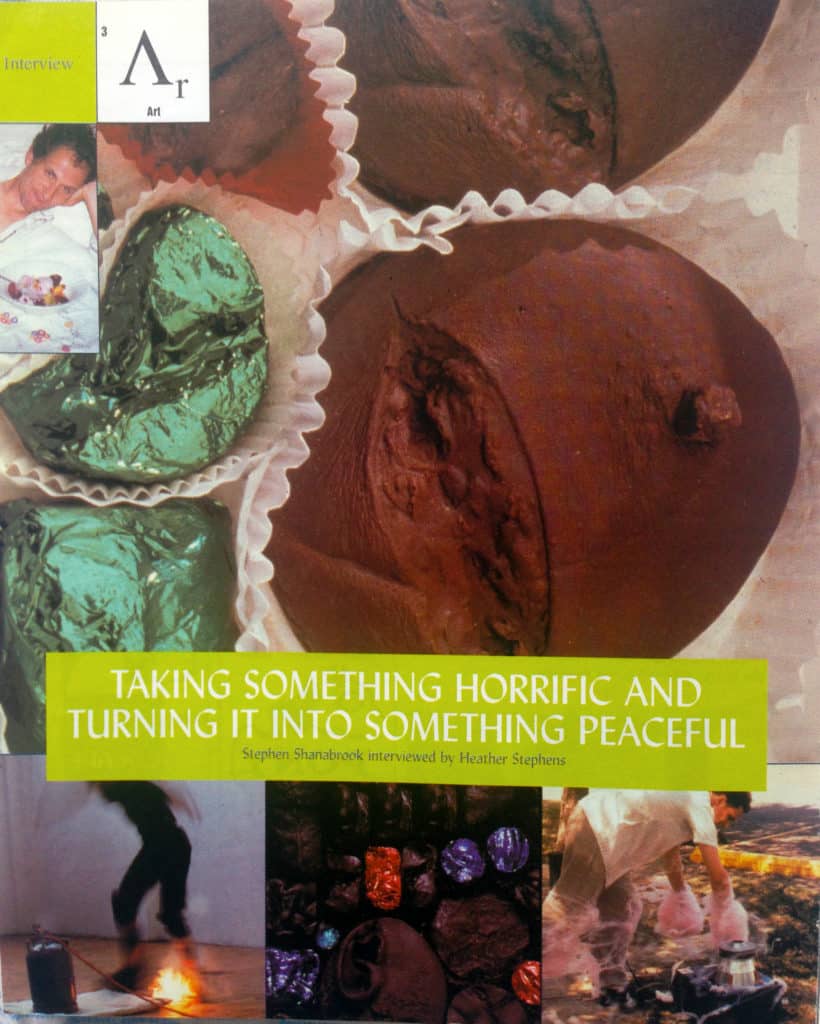

Consumption alone has become the manner in which life is sustained. In this state life’s processes can not come full circle. Upended in a single direction, movements both physical and psychological become stilted and reactionary. The chocolate molds were made from impressions collected at morgues in both Russia and America. Through the hint of digestion or thought, these wounds structured superfluous in chocolate are temporarily removed for the living to process again, not to acquaint us with death per se, but to nourish life in the sense of connection to. It goes without saying that barriers are relieved of their duties when one makes a connection between body temperature and the temperature of chocolate or associations with religious practices and biological orders. But laying a grid over chaos seems nonsensical; it chaos, seems better understood through the making of such connection.

Morgue Chocolates Editions Titles:

Unidentified *

Evisceration of Waited Moments *

Halcyon Nest / open eyes **

Halcyon Nest / closed eyes **

* 8 lb. chocolate, 51 x 46x 6cm, edition of 25 boxes.

** 2 lb. chocolate, 34 x 27 x 3cm, edition of 50 boxes.

All editions are delivered with pure dark chocolate and one refill made

from chocolate, wax to enable permanent shelf life.

Samuel Johnson once wrote: ” He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.”

Stephen j Shanabrook’s new sculptures are reflections of this endless battle – between human pain and a beastly take-over. It’s not a judgment, it’s more like an emotional surgery, the frozen moments of this fight club, of chasing the dragon. Stephen’s renowned technique of melted and pressed plastic is a powerful translation into the visuals of a surrealistic nature of influenced mind. In the ” Throw-up” Series the combination of melted plastic and human face masks express a disturbing struggle between the figurative ( the pain) and the abstract ( the beast).

is a Series of Performances in the metaphorical sense about the discontinuity in living portrayed through an action of pure experience with its aesthetic roots in childhood. Bandaging a wound is the first step in the recognition of, and the commitment to, hope and a step forward. After the bandage is removed the wounds’ memory stays with us in the form of a scar, which becomes a permanent reminder.

The cotton candy machine comes from the celebrative and festive times of the formative years, the dog days of pure experience. By wrapping my hands in cotton candy (sugar) that consequently is liquefied by the sun I propose an opening to past pure experiences. The sugar now a sticky syrup (blood) eventually becomes crusty, like a scab that forms giving way to the scar. This action searches at the point where reality exchanges with the ideas and events of the past; here the object head or action disappears or at least ceases to be relevant. The event begins when the hands of the boxer are wrapped, it ends when he has fallen to the ground, in the bright lights he holds his position until the gloves melt away gradually with the regaining of consciousness. Inherent in this action is a simple directness that leaves open a mind path for the viewer, giving their ideas a space to ferment.

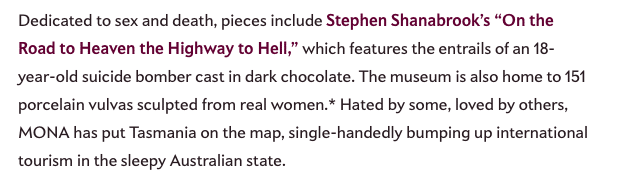

FLAT GESTURES OF THE TROUBLED MIND / MELTED PLASTIC SERIES

Everything you are forbidden to do as a child – wrapping cotton candy around hands, pumping chocolate through electrical outlets, breaking thermometers for the mercury, casting the dead into chocolate delicacies are all endeavors I have partaken in as an artist.* In my new exhibition “ Hell and Back” plastic figures and plastic pieces are put into a commercial oven, brought to their melting point, and then pressed into a flat frozen eternity, in short, an instant fossilized still life of the contemporary culture.

Inherent in this process is a battle between chaos, control and chance, with each condition leaving its trace on the final outcome. There is a fine line between letting the plastic porn star dissolve into nonentity and stoping her in the last breath of beauty. These pieces freeze frame the transition from liquid into solid, from figurative into abstract, they animate the stages of beauty on the threshold of death and disaster. Soft then hard again these deformed variations of toys transformed into their own monument, into gravestones of the culture that bore them.

« … but here the monument is not something commemorating a past, it is a bloc of present sensations … The monument’s action is not memory but fabulation. It is not memory that is needed but complex material that is found not in memory but in words and sounds : « Memory, I hate you.»*

Therefore I burn! Using the same process, of temperature and pressure, nature creates precisely such memorable monuments – oil, fossils, diamonds, and carbon. While in my geology of expedited action, frozen plastic magma, these “ useless” minerals ( which remind us of a page from comic books based on Dante’s adventures in hell ) are impressions of swiftness and shallowness of contemporary culture that create mass-produced products. Hundreds of identical objects, which are dying, through their suffering of sameness priced for the global market – none of these figures melt the same so in their death they achieve individuality.

* Deleuze, Guattari « what is philosophy?»

Who is he? Modern society increasingly demanding from us to make reasons and choices, making us believe that each step, each choice will lead us to a better set of stairs and next better choice to an even better place, etc. The Traveling Idiot doesn’t want to make choices, he prefers to make gestures while wandering around. He is neither a winner nor a loser, he refuses to make the distinction and expects fate to sculpt him. His journey is chaotic and yet leaves behind seemingly useless but funny traces of personal destiny. The show Traveling Idiot is a collection of those traces. Orchestrated as a road movie The Traveling Idiot is devoted to the moments of emotional gestures, the sought after “mistakes”. The morning with its’ regrets and clean-ups hasn’t come yet. It’s still time for the choice-free, guilt-free ride.

It’s something similar to that moment which Bukowski finds in drinking experience: ” I have the feeling that drinking is a form of suicide where you’re allowed to return to life and begin all over the next day. It’s like killing yourself, and then you’re reborn…”. Like in “slapped in the face till your shit turns red”, a performance with a cotton-candy machine, where Stephen Shanabrook put his face so close to the machine that sweet pink mass of cotton-candy plays the role of a powerful weapon. And aftermath looks like a scene of that “temporary suicide”, which Bukowski is referring to. The artist combine materials with such reckless and similar type of gestures, such as one where Martin Kippenberger painted his Ford Capri in brown paint imbued with oatmeal.

an 8 min. video, made with a camera mounted to the wheel of a car. The viewer is seeing the streets of a summertime South Bronx from a tire’s point of view. While the car moves slowly the narrative is linear and recognizable but as the car gains speeds the narrative turns abstract into a kaleidoscope of color and form. This traveler just seems to wander around, being “lost” staying on the periphery of things, and being happy about it. ” Why humbly to be melancholic about the center? Isn’t the center, this absence of game and diversity, just a different name for death?” – says Derrida.

In his book “Ways to the Paradise” Peter Cornel is comparing two classical texts based on pilgrimage – by Chateaubriand and Gerard de Nerval*. Chateaubriand’s travel is linear because his catholic faith has no doubts. He knows the Center and directly goes to the main pilgrimage locations: Rome, Athens & Jerusalem. Meanwhile, Nerval is traveling on the periphery of those centers. His East “is an uncertain magnet field, without a center or ending point”. Chateaubriand is more like a tourist while Nerval is a traveler. Our Travelling Idiot goes further, he is not just ignoring the Center and directions, he is basically killing them.

In the new series called “Get Directions” the artists had blank road signs made for them from the Department of Transportation in NYC. These blank signs are used as a canvass on which traveler’s gestures are recorded, they lead you nowhere with the intention to get you somewhere.

by RENATA SALECL.

What has changed in today’s perception of travel? What does a journey mean – when we have so many choices of where, how, who with, – and of course, do we have to travel anywhere at all ( perhaps we prefer to travel in our fantasies, or we follow other people and fictionally travel with them)?

Robert Frost in his well-known poem “The Road Not Taken” writes about an individual who is standing at a crossroads, and after deciding on which path to take, he chooses the one less traveled. Today, we not only stand at the crossroads of two paths, but too often we stand at many fast roads, and the decision on which to take becomes even more difficult. Stephen j Shanabrook tries to point to the problems of the modern individual who constantly lingers between being some sort of a tourist and taking the supposedly safe straight path, r being a traveler, who roams the periphery, and who simultaneously sees and feels many shades of life around him. What from afar seems like a beautiful Oriental carpet turns out to be the imprints of garbage. The prints of tires on an empty road are nothing more than smeared chocolate. A look at the surroundings in which we drive becomes a confused smear if we position ourselves in the field of vision of a wheel rushing through space. That is, we must always keep a certain distance from the surroundings through which we pass in order to form a likable story about us.

How can we keep this distance? Shanabrook suggests that the traveler assumes the role of a traveling idiot. A person thoroughly assumes this role when he no longer wishes to make decisions, but simply surrenders to the signs and gestures seen along the way. In the Luke Rhinehart novel, The Dice Man, the main character decides to make all his decisions with the throw of a dice. Such a surrender of the flow of life to chance may seem liberating at first. However, in the end, the dice acquire almost mystical power, and the hero gradually sinks into madness.

In their project, Shanabrook uses blank road signs that lead nowhere but simultaneously function as canvases on which the traveler records the signs and gestures seen on the way. It is because the road signs show no directions that they lead us towards a constant attempt to comprehend the gestures and signs around us, and hence, persevere in the hope that perhaps we may discover how and where from here. Because the road signs lead nowhere, and because we can manipulate them (turn them over and over again in a new direction), we are forced to create our own, but always temporary, a system of signs. Above all, we are constantly forced into the role of an interpreter of the gestures of other people that we meet along the way. But because gestures are so very personal and usually even the one making them does not know what they convey, we are always at the beginning of a path – for we do not know where we are actually going, as the path doesn’t have clear directions, and because we always end up elsewhere than expected.

And where are we supposed to be going? Jacques Derrida said that people too quickly become melancholic because they cannot reach the center. He asked himself if the center, this absence of game and diversity, is not just a different name for death. The Traveling Idiot hopes, by walking around the periphery, to be able to avoid the dreadful center, but in the end, is nevertheless consumed by the center. And what print is left afterward? Perhaps only a smear of chocolate.

is a Series of lightboxes of garbage cesspools from an abandoned construction site in Moscow center. The image was multiplied and reversed in such a way that it is reminiscent of oriental rug patterns. The beauty of water has similarities to the beauty of an oriental rug — one can look at it for a very long time and become lost in its’ intrinsic meditative journey. Although the visual beauty of this Carpet is counterintuitive, because of what it is really made out of — rotting garbage, dirt, and sewage in a polluted pond. The irony of the image is that the pool contains used plastic bottles of drinking water. We dump so much inside of it, that the Water becomes heavy. It’s a metaphor for both: our planet (external) and our memories ( internal). To live surrounded by polluted water as well as with polluted memories it’s like trying to carry The Carpet Full Of Water: what was easy and simple becomes heavy and smelly, a burden.

PRESS RELEASE: LIQUID LUSHES and LATE NIGHT HOUSE of PILLS

Looking at Stephen j Shanabrook’s work is like watching the horse jumping over an obstacle and instead of landing on the other side it starts to float and you are lost. Like a man on the wire Shanabrook restlessly walks the disturbing line between heaviness and zero gravity, between painful and sweet, death and beauty; melting them together, metaphorically and literally into one frozen state, one fossil. In « Hopping Hills, the Pharmaceutical Landscape» the artist melts plastic RX/pill bottles and presses them into the form of easter bunnies. Installation with running and hopping rabbits made out of hundreds of empty pill vessels suggests that prescription drugs became the new religion, an American side effect on its own – as a result of lost hopes and multiplying disconnections with reality and between people.

In Shanabrook’s sculpture «Island of the Lotus-Eaters” the viewer is seduced by the beauty of a huge flower, which with closer examination becomes again just a pile of melted drug bottles. On his long journey back home Odysseus visited the lethargic island of Lotus-Eaters. The lotus fruits and flowers were the primary food of the island and were narcotic and addictive. Lotus-Eaters entertained Odysseus’ men with the drug causing them to forget about their strong desire to go home, now they only wished to stay and eat more lotuses. The labyrinthine journey back home is a metaphor for our life. And the drug illusion has the tendency to bring us «home», but most of the time it’s a wrong turn on a slippery road and often a fatal one.

Shanabrook isn’t a stranger to the addiction, he went to hell and back on his own. A mix of materials in a non-stop experimental process, which for addictive personality is never enough, in combination with themes of longing for home strongly reminds us of another mover – Martin Kippenberger. With similar types of gestures, like one when Kippenberger painted his Ford Capri in brown paint imbued with oatmeal, Shanabrook covers common plastic soldiers in delicious dark chocolate in his new installation “Battle of Losers and Lovers”. The sweet, desirable chocolate drippings on the white surfaces stacked on each other office tables, the symbol of the everyday working process, become messy bloody evidence of fight and satisfaction.

In his rather horrifying statement “The Chocolate Soldier or Heroism – The Lost Chord of Christianity” C.T. Studd (1860-1931) called “ a soldier without heroism is a chocolate soldier! ..dissolving in water and melting at the smell of fire. Sweeties they are! Bonbons, lollipops! Living their lives in a glass dish or in a cardboard box, each clad in his soft clothing, a little frilled white paper to preserve his dear little delicate constitution.” More than a hundred years later we understand that it should be a place for all – chocolate soldiers, losers, and lovers. While and especially because society puts so much pressure on people’s lives, every day feels like a battlefield. And at the end of the day, we want the prize, we want chocolate, we want home. Shanabrook remembers “…reading an account of a field medic from the Vietnam War. He was explaining what he carried with him in his medic satchel, these bare necessities as he called them included: gauze, morphine, tape, comic books, and M&Ms. The candies were for the mortally wounded soldiers, the ones that would never make it to the field hospitals. For these soldiers, the candy was a way to satisfy a simple desire to feel closer to home, before they slipped away into that unknown jungle.”

The MOTH COLLECTION uses a common entomological setting, to lay bare the hubris of narcotic use. Using the shade of night the moth and the addict share their obsession of getting closer to the light, that light which can on occasion eradicate.

The L.O.V.E. as a List of Vicarious Edges – these bandages are not healing the wounds, but instead conceal the source of pain i.e. the weapons (blades, needles, shards of glass, etc.). L.O.V.E. is a flag that reveals a territory of hidden pain.

SLEEPING WITH CHOCOLATE/autopsy table a self-contained unit, where chocolate is pumped to the surface and returns through a middle drain / 1996

A bed is a private space made public through its transformation into a hospital bed or autopsy table. Displaying this night-time lesion opens a kind of wound, a dream which lays bare the soul through the show of chocolate. The bed contains a heart that enables the perpetual flow of passion permeated by death to be equated in life and forgo putrefaction. The chocolate oozes from the mattress’s surface to be purified by the air and light of the viewer. Chocolate and blood function at similar temperatures and as fluids they both have come down through history as offerings to the gods or at least as remedies for curing some inner melancholy.

THE MEASURABLE LOSS OF WATER DURING A BIRDS’ FLIGHT/ Flevoland Polder, Netherlands / 1996

This action on dehydrated land on fields of winter wheat and seashells seeks to converse with the language of loss. The text offered up by means of a helium balloon is concerned with the idea of water loss through language. The body like the sea here before is made up mostly of water, so it is speech or the movements of words that augment our steps forward. Moving through time the body loses water both literally and spiritually like the turning of relationships and conversations. All of human history is tainted with this notion of keeping oneself moist or fluid.

PUBLICATIONS

Franchesca Alfano Miglietti ( FAM )

BOOK “ Extreme Bodies. The Use and Abuse of the Body in Art.”

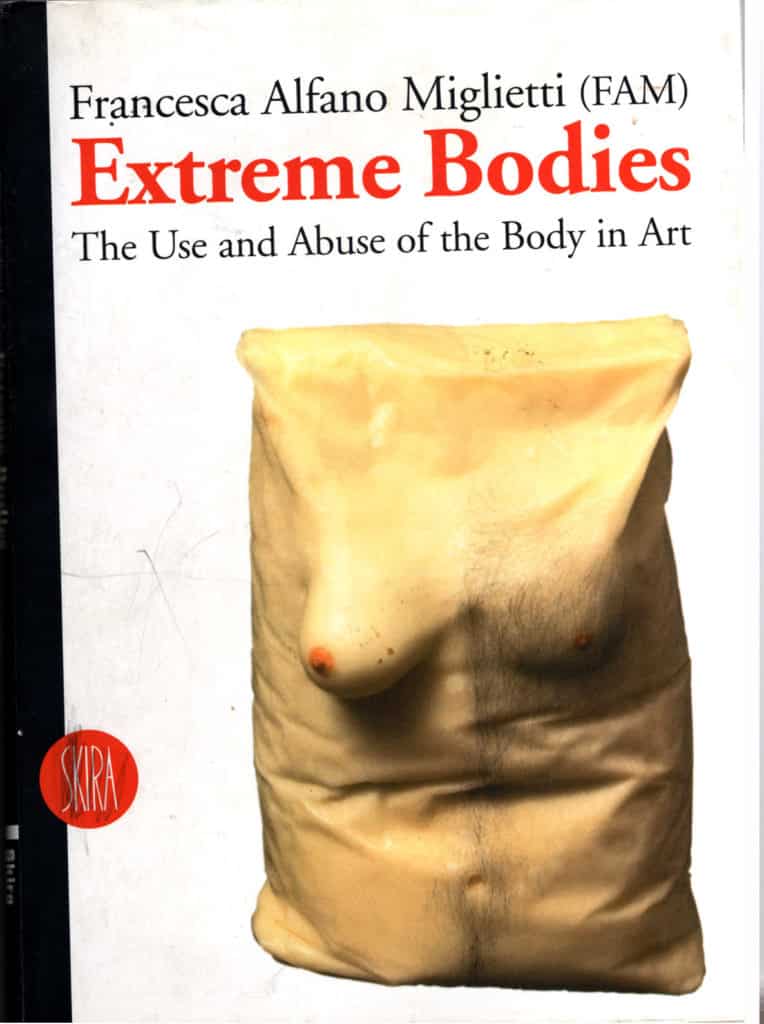

“ My relationship with chocolate in an autobiographical sense comes from when I worked in a candy store. Careful you don’t’ melt, candyman! they would say to me when I would go to take a shower after football practice. Later, at university, when I began to formulate my artistic language, I started using food as the temporal element of my pieces. Immediately after university, I completed my first installation, developed with chocolate in a slaughterhouse. In general, my artwork consists of different works that use chocolate as a fundamental ingredient. Looking at and smelling the Morgue Chocolates, a spectator tries to distance pleasure from himself or herself. For me giving the spectator a complete vision of the artwork means making him or her work with all five senses”. Stephen j Shanabrook is an American artist who lives in New York and Moscow. Some of his early pieces were done with sugar and sweets, but it was with ‘ Unknown Resurrections’, using chocolate, that Shanabrook’s work became radical, aggressive, powerful. He intertwines and merges two metaphorical shadows that have nothing in common: chocolate and wounds. Two metaphorical shadows, of the metaphor of chocolate, joy without sin, and of the metaphor of death, sin without joy. The symbolic meaning of chocolate, linked to the imperative of pleasure, and the symbolic meaning of the wound linked to the dimension of pain, creates a sort of disorientation in Shanabrook’s work, an effect of nausea, waste, sabotage, and excitement.

Sickeningly sweet remains that are in no way symbolic like the recognition of something which we are incapable of understanding, like the very substance that sublimates fear and beauty, in which we find the renewed emphasis of the paradigm that art is stronger than death. Chocolate casts that in aesthetic terms lose track and reference to the proportions of “good taste”, and which in ethical terms present themselves as an imperative of the ego that demands that we hold out to the very end, whatever it cost. For the American and Russian series, Unknown Resurrections, Shanabrook chose the bodies of the “different ones”, those whom society tries to repress or insult because they make us feel uneasy. These lives and the traumatic experiences they have undergone are the motifs of Shanabrook’s casts. A detailed description of body parts, living evidence of the end, impersonal parts of injured bodies, that have been shot, crushed or stitched carelessly back together, which can only be classified in accordance with the findings of forensic medicine. These casts, made in Moscow, look like so many chocolate bonbons laid out in a sampler box, a vision of violent death rendered peaceful and consumable by the decision to make the casts in chocolate. The bonbons of the Morgue Chocolates series are the asymptomatic product of the artist’s vision of life and death in America: the remains of people who have been brutally murdered, bodies that could not be reassembled, constitute a “silent lament”. Gunshot wounds, protruding eyeballs, knife wounds stitched up with ordinary string, in his work become so many fragments of a horrible and everyday reality that hits us in the solar plexus through the precise little casts made of chocolate. This vision and this presence of violent death in “chocolate” frightens us and irritates us, much more than the death that we witness daily in the pages of the morning newspaper and the evening television news: 32 casts of an eye in the box of Halcyon Nest seem to be covered, through the chocolate, by an inevitable death, a series of eyes open and sleepless that seem to want to affirm the refusal to die, an inability to resist and, at the same time, the suggestion that in the face of violent death we cannot close our eyes.

And once again art chooses the rejected, the unwatchable, the close-up. It is precisely the banality of chocolate that renders the image so powerful because the spectator is caught by surprise. The familiarity, the odor and the sensory stimulation of the pleasure that the chocolate provokes are the influential aspects of the Morgue series. A cloying and banal package of chocolate bonbons, which reproduce a case of gangrene, a gunshot wound, a suture of lacerated tissues, is seductive and stimulating, and until the horror takes over it is desirable. Even if we don’t admit it rationally, the desire is there and so, for the spectator, the conflict begins: the odor of the chocolate is so powerful that he cannot manage to face what he sees, even before he begins to ask himself exactly what he is seeing. As Gilles Deleuze has written:” … every man who suffers is flesh. The flesh is the common territory shared by man and beast, and indistinguishable territory, the flesh is this ‘fact’, in which we identify with the objects of horror and compassion”. The sensation and the impact are powerful, clashing, disquieting, and seductive. We feel guilty, we feel the disagreeable sensation of wanting to eat the proof and the outline of someone else’s pain. Shanabrook makes chocolate shapes that are apparently similar in their manufacturing and in their visual impact, to those ordinarily available on the market, and he uses as containers the “classic” gift packs: but the decorations on the chocolates themselves, customarily signs of a roguish and popular romanticism – little hearts, flowers, and cameos – instead reproduce the signs of the abject within the superficial pleasure of the taste buds in order to provoke a complex imbalance: remembering life through the contact with the death of another. “Consumption has become the way in which life sustains itself. At this moment the process of life does not close its circle. It goes in a single direction, the physical and psychological movement becomes reactionary and artificial”, states Shanabrook, who sees in chocolate a close relationship with the idea of blood, both fluids that have passed through history as offerings for the gods or as a simple remedy for inner melancholy. After his first performances and exhibitions, in which he utilized only his own body, the artist began to work on other identities and other anatomies, including dead bodies, always using food as a metaphor for the human condition; nonetheless, it was with the Morgue Chocolates, the artworks made of chocolate that contain signs of wounds, death, and those of the internal workings of the human body after death that Shanabrook begins to approach the limit, the place that is forbidden: the place of the artist. These pieces of chocolate represent the dichotomy that is always present between life and death: utilized both the sensory stimulations of taste and the “information” of disgust in the rational sphere, the spectator finds himself or herself trapped in that dimension in which things, sensations, and attractions have no name and are nothing more than a sum total of opposites. “While I was working in the Moscow morgue, the idea of identity was not particularly important to me, because it was a morgue for unidentified people. In fact, the title of those works was Unidentified, and this word or a derived word was usually written in green on a leg. Moreover, in Moscow, when I first exhibited these artworks, I presented them intentionally in an old information kiosk not far from Red Square. In this way, the identity of the corpses was replaced by the identity of the living people through their oral or visual participation”. One year after the presentation of Unidentified, Shanabrook exhibited Evisceration of Waited Moments, in which all of the images of death are “taken” from an American morgue. “ The situation there was quite different. I was extremely aware that I did not want to be involved in the past of these corpses. What I was doing was intended merely a as a way of representing death in general, not in particular, not in any connection with a specific personal history. Concentrating on the narrative part would have been an unacceptable invasion of privacy and would have added only a component of shock has no value or purpose and undermines the work, taking it down to the level of a scandal rag. The pieces of chocolate are generic representations of death, and for me, they need to remain anonymous in order to preserve their universality and their cutting edge”.

A later series involved the production of masks of young Russian poets done in chocolate, creating a powerful emotional impact in their manufacturing simulating the form and the fixity of death masks. Once again the main theme of the artworks is the link between life and death; in place of chocolate surrounded by violence, we find that it is poetry that now surrounds the chocolate. Restitution after the Meeting of Thirteen is an artwork executed with the co-operation of twelve Conceptual artists from Moscow: Shanabrook exactly reproduces the faces of each of twelve artists, and then all of them are given an exact copy of their face in chocolate and their index fingers in graphite. Each artist is given 24 hours to interact with the face as he thinks best, recording what happened on a piece of paper specially supplied, using his graphite finger as the main writing instrument. “ My role as an antagonist ( the thirteen one) consisted of presenting the artist as a conflictive being, rendering his image desirable and digestible even if this meant in some cases inflicting a form of self-destruction, or taking revenge on one’s own ego. Given the quality of the chocolate I did not expect that I would have many remains to display, but to my great surprise that is not at all what happened: at least half of the artists chose not to take part in this act of virtual cannibalism…” The chocolate masks are conceptually very similar to the Morgue Chocolates: the invitation to take into consideration the meaning of what it is to look at one’s own death mask triggered various interventions, even though all the artists who took part in the project left on the masks clear signs of an inner conflict, a sort of restitution to their own funeral effigy of the most vital part of their own being. In Shanabrook’s vision, the use of chocolate takes on the value of a very powerful weapon, since because of its ordinary and desirable appearance nobody is afraid of chocolate, “ indeed, the first thing that comes to the mind of most people is to eat it, while in a second phase they discover the message that I meant to hide in it. And there they are, like fish on a hook”.

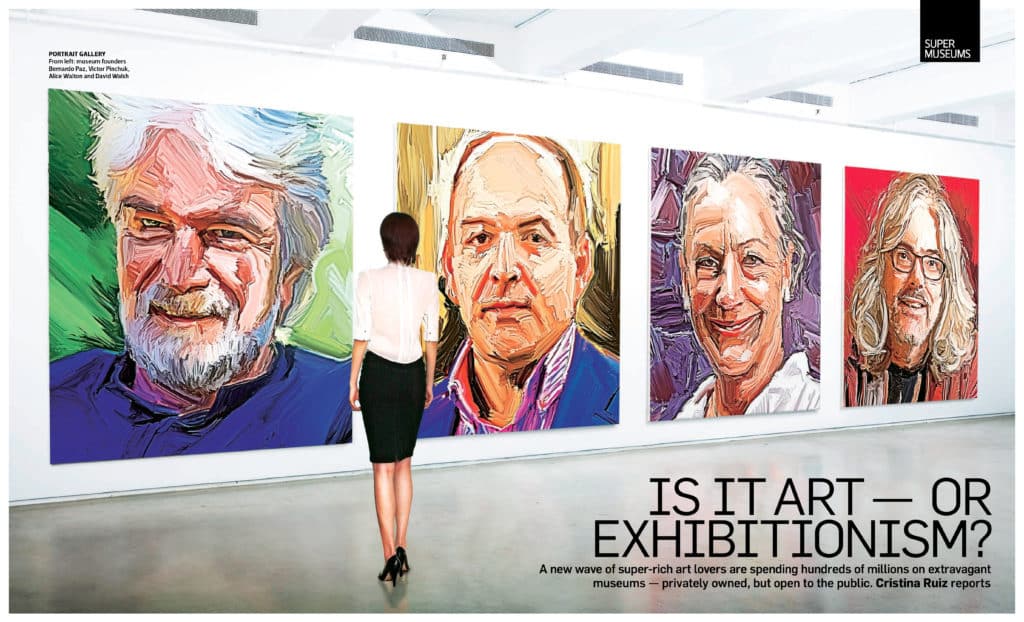

SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Katherine Carl. Common Destination.

Stephen j Shanabrook traverses the taboo terrains of desire and violence to explore their paradoxical common ground. He specifically focuses on the material qualities of these states to conjure a transformation that makes a surprise out of tangibility. He has, for example, spent time in a morgue in Moscow, making casts of fatal wounds and then creating chocolates from resulting shapes – bonbons, as it were, of mortality – and he has perforated Wallpaper with gunshots to produce even more beautiful patents. In Memory Confetti Series (2006), he applies an alchemical approach by shredding drawings made on acetate and then jumbling them in a viscous emulsion to make colorful projected kaleidoscopes. In earlier artwork, Shanabrook often made traces with indeterminate fluids, such as melted chocolate, that are mistakable for blood or oil, an effect that is as viscerally potent as it is politically resonant. These playful works of vanitas subject materialist obsessions to processes of chance in a pungent comment on both consumption and the materialist discourses of communism and socialism.

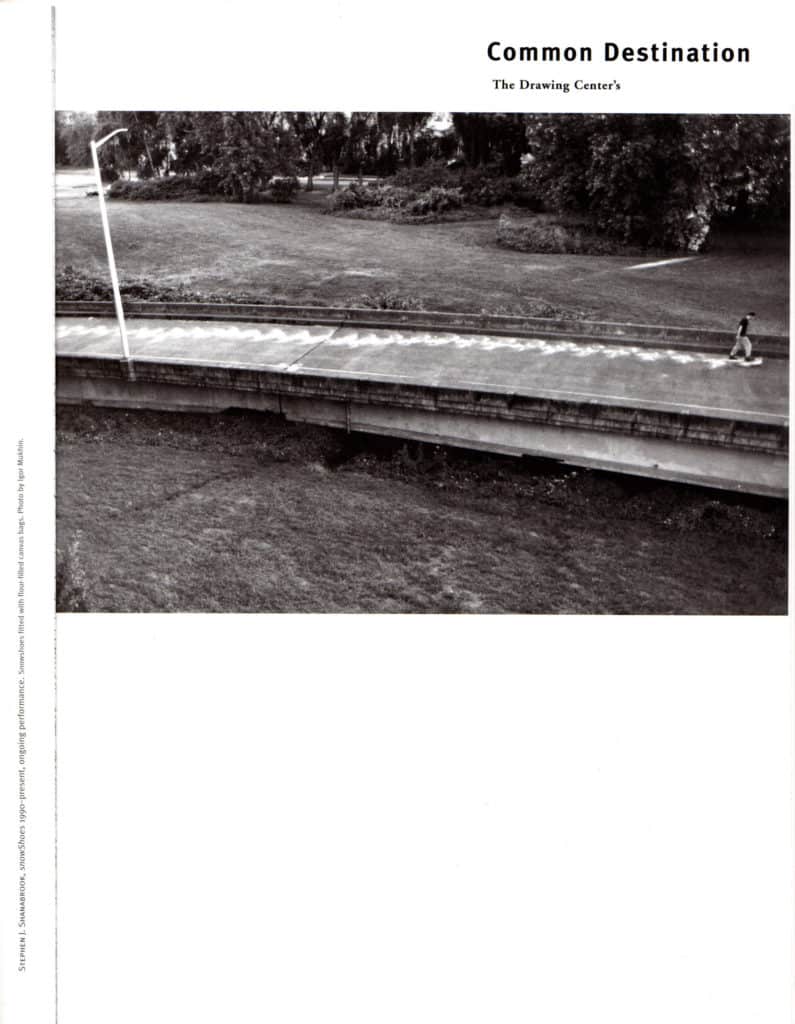

Shanabrook does not predetermine his marks, which are sometimes made as part of a performance. He uses dusty surfaces of chalk, flour, and graphite, all of which can be scattered or smudged. In his Walking Works, Shanabrook plots traveling routes, sometimes through public spaces and other times within a small confined square of material in the gallery. He has walked through the streets of Amsterdam in snowshoes, extruding wisps of flour, and he used a cane to tap out his path in the streets of Moscow, leaving phosphorescent marks to help him to find his way back. In a gallery space he has walked with Dutch shoes covered in felt on a square of graphite. Like children’s fairy tales, these works tell the magical story of life’s long journeys and fleeting moments.

Shanabrook marks territory to trace and delineate his own life crossing, its expansion throughout time and space. He makes his own path visible, and for those who are quick, he leaves cues of recognition to welcome fellow travelers.

INTERVIEWS

BLEND MAGAZINE

INTERVIEW VIRUS MAGAZINE with JURIJ KRPAN

Jurij Krpan: I’ve seen some early projects dealing with sugar and sweets in your portfolio, but exhibition of chocolates named “ Unknown Resurrections” showed in Kapelica Gallery is not alike to any of them. Why you decided to overexpose the almost banal material of chocolate with such a radical topics? Was that fact also a statement considering your former, much easier works?

Stephen j Shanabrook: It is exactly the banality of the chocolate that makes the image so powerful because the viewer is caught off guard. The familiarity, smell and the hidden psychological effect of chocolate are the most influential aspect of the morgue chocolate series. By exhibiting wounds in a chocolate box motif, the mold of a shotgun wound to the face becomes desirable to the viewer. Even though one would not admit it, the desire is there, and so begins the conflict for the viewer. This smell is overpowering to the point were one can not come to grips with what one is seeing. So much so that you begin to wonder what you are really looking at. How is it taht we should desire to eat the representation of others pain. The chocolates are made in sense to be digested mentally or physically removed for the living to process again, but not to acquaint us with death per say but to nourish life, in the sense of connection to . “ Consumption alone has become the manner in which life is sustained. In this state life’s processes can not come full circle. Upended in a single direction, movements both physical and psychological become stilted and reactionary.” ( from “ Morgue Chocolates” series statement SjS ).

Furthermore, chocolate and blood function at similar temperatures and as fluids they both have come down through history as offerings to the gods or at least as remedies for curing some inner melancholy.

JK: Your former artistic actions and exhibitions did not include a human body beyond you alone. How you decided to work with bodies of other people and why with dead bodies? Did you have any references considering all that “ body art” heritage from the past?

Sj S: The direct use of the human body in my work was not the ideological leap that it may seem. Most of my work prior to the morgue chocolates dealt with food either as material or as a metaphor referring to the human condition. Conceptually speaking the formula from which these works spring is that food is to humans; as nature is to the soul. The morgue chocolates materialized after the edition of chocolate teeth called “ I eat people they eat me”. This edition was made from casts from teeth collected by dentists in Holland and Amerika. But the teeth were only half of nature, I wanted to work the whole. To do this, one must speak about the other half i,e… death. So I decided to make chocolate editons that contained impressions from the wounds of death and impressions of the internal workings of the human body ( after life). At this point I realized that this piece was very close to the edge, the forbidden place for artists. But herein lies its strength, these chocolates speak about the ever-present dichotomy between life and death. Weather through the stomach or the head the chocolates bring the viewer into the circle of nature, one that contains the pain and happiness, one where things have no name; just opposites.

JK: How did you manage with identity of the corps? Is in yoour work any reference to a particular person and his life story? After all you had worked on a whole corps in the morgue.

Sj S: While I was working in the morgue in Moscow the idea of identity wasn’t relevant because this morgue was particularly for unidentified persons. Hence the title of the edition “ Unidentified”, this word or a derivative of was written on the body usual the leg with a green marker. Furthemore in Moscow when these chocolates were first shown, I purposely exhibited them in an old information kiosk next to Red Square. In this way the identity of corpse was metaphorically supplied by the living through their partaking orally and or visually. A year later I made a new edition “ Evisceration of Waited Moments” from a morgue in America. The situation there was very different in terms of identity. I was very conscious at that point while making the molds not to be involved with the personal past of corps. The impressions I was making were only to be representations of deathin general not particular or with stories. Concentrating on the narrative as it were, would, I feel be an unacceptable invasion of the privacy and should only add a useless shock value. When dealing with such matters I feel strongly that shock value has no place or purpose, it only degrades the work down to the level of a supermarket rag paper. The chocolates are the generic shadow representations of death, for me they must stay anonymous to keep their universality and poignant.

JK: But the series of masks of still living young Russian poets made by chocolate wears a strong impact even that they are alluding post-mortal mask. In that project the connection between life and death is more polite. I guess. Instead of chocolate wrapped in violence the chocolate masks are wrapped in poetry. Why poets?

Sj S: It was actually only one poet. “Restitution After the Meeting of Thirteen” was a collaboration between myself and twelve well-known Moscow conceptual artists including a poet and a writer. The artists ranged in age from 22 to 63, this spread of generations I felt was nost conducive for achieving the truest response to the project. Each artist was given an exact replica of their face in chocolate and their pointing finger in graphite. They were then alloted twenty-four hours to interact with their mask in the manner tehy deemed fit and to record this interaction on asupplied piece of paper, using their graphite finger as the main writing tool.

In the face or more particularly the eyes are the windows to the soul and the eyes ( in this case) are closed, is it not then, that the artist is only confronted with a representation of the ego. My part as the antagonist ( the 13th) was by presenting the artists with a conflict in the sense of making their representation desirable, digestible ( mentally or physically) even though it meant in some cases a form of self-inflicted destruction or revenge on the ego. Considering the quality of the chocolate I didn’t expect to have much left-over to exhibit, but to my amazement the contrary was true, almost half of the “chosen” didn’t partake in this self representational cannibalism. These masks as chocolates are very similar conceptually speaking to the morgue chocolate, when on etakes into account that all the artists felt a notion of looking at their death mask. This was as you say more polite visual spaeking, but at the same time it dealt more with an inner conflict, the sword was turned inwards on the self and we all know the devastating power of inner conflict. The manifestations of these conflicts are overall to be seen and heard.

JK: After all it seems that using the chocolate is like using an powerful tool. Because of it common and desirable appearance nobody fears it. On contrary. Almost everybody first thought is to eat it, but in the next moment they discovered the distractible message that your “candy s” wear. They find themselfes like fish on the hook. Looking at your work seems that it works from the stomach. Are you “poisoning” your audience? Maybe there is an autobiographical note hidden?

Sj S: My relation to chocolate in an autobiographical sense stems from my formative years, when I worked in a small candy store.

“ Watch out you don’t melt candyman”, they would say to me before I would get into the shower after football practice. Later in university while formulating my artistic language I bgan using food as a temporal element in my work. Soon after leaving university I made my first elaborate installation from chocolate goat fetuses stirred by my job at a slaughterhouse. In general my oeuvre consist of several works using chocolate as the main “ingredient”. As with the other materials I use , they are chosen for particular conceptual reasons depending on the striven for outcome. While walking down the street in the summer it was the strong smell emanating from the candy store that began my desire to work there.

Now I am sick to my stomach ( listen through your nose, feel with your teeth)! Chiocolate has a physical and psychological Pavlovian affect on the viewer, and this anticipation is sometimes more satisfy than tha act itself. Looking at and smelling at the morgue chocolates the viewer tries to hide the pleasure from thenselves. For me to make for the viewer the most complete vision, then one must speak through all five senses simultaneously.

INTERVIEW ZAVOD 21 by OLGA MAJCEN

OM : can you explain your work Stephen?

SjS : can you ask me a better question?

OM : No.

SjS : Okay the piece I exhibited for Break 21 is from my morgue chocolate series. These are the American edition “waiting for eviscerated moments” A series of casts from wounds I made in chocolate wrapped in papers, colored foils the like and presented in a chocolate box …ready to eat.

OM : How did you get this idea?

SjS : Honestly I should say that it came from everything that came before. To the point it originated from another work called “I eat people they eat me” this was an edition with three chocolate teeth cast from real teeth pulled by dentists in America and Holland. When I was asked to go to Moscow to exhibit with Russian artists the curator told me about the Red October chocolate factory in the center of Moscow. Thinking in those weeks prior I somehow got the idea to work in the morgue, in the back of my mind knowing if it was possible… this time Russia was the place.

OM : what did you find fascinating about morgue and wounds?

SjS : In the morgue nothing and everything. But most disturbing was the smell. I didn’t realize that until I went to the chocolate factory, it had the same overpowering sweet smell. Actually I had so much trouble doing the morgue works, I mean from people around me. They thought I had crossed some boundary that shouldn’t be crossed. I actually had some of the same doubts probably because of the situation but the visit to the chocolate factory brought the whole project full circle for me, in the sense of connecting life and death. For me it was O.K. Because the smell was the same. The wounds per say were just the medium for a message they were my means to something. I had been working with them in one form or another in various pieces for a long time.

OM : you said that you didn’t realize the difference from the real world and the morgue until you came out, can you tell us something about that?

SjS : I had a very particular purpose when I came into the morgue. No matter what I saw, no matter how overpowering it was… shocking or “unreal”, it didn’t really hit me, until I left. I walked out the back door of the morgue looked up and saw a huge tree that I remember very clearly, and then it hit me what I just did, what I just experience. A half hour later I threw up on the metro on the way home. I suppose it was the contrast or the fight of life and death.

OM : what are the differences among the morgues you’ve been to?

SjS : Actually. Visually there is a huge difference, but the psychological nuances of how they work are the same.

OM : How did you pick up the parts of the body that you wanted to make casts of?

SjS : In general I looked for details that showed some destroyed element of the human body. Forms that could give maximum information but be kept small in size so that the illusion of the chocolates in a box would work better. Because this is pivotal with the intensity of this project, in the sense that, the more these chocolates appear to be your average chocolates in a box, the more powerful the insight becomes on closer evaluation. Because in the end it is the ordinary things that are most shocking when looked at from askew.

OM : do you know the story of everyone that you took casts from?

SjS : I do more or less of the American edition just because I was around the doctors when they were doing autopsy. I tried not to pay attention. Because I didn’t really want to involve myself on a personal level, who, how and why this person died, it wasn’t about the personal person. It was the “general” wound, the psychological wound.

OM : Were there some interesting stories about deaths?

SjS : Of course there is always something interesting when you are with death. the shadow of living. But actually in the contexts of chocolates, these stories are only distraction.

OM : In what way did this project change your perspective to death, if it did?

SjS : my perspective of death just became more in the realm of reality, but what it did change is my perspective of how entangled life and death are…. like how close beauty and horror are and how the lines that separate these things are jagged and hard to defin

OM : Why is you wanted to make a chocolate out of wounds.

SjS : because chocolate is so desirable. The working temperature of chocolate is the same as body temperature so there is something comforting about it as a material. Also it has the same color of blood in black and white images. Like the famous shower scene from Hitchcock’s psycho, the blood is chocolate syrup. It is a foodstuff – an unnecessary one at that– food for the gods. Something that people need to have once they smell it. I felt like that was the meaning of my need to use this chocolate because of this horrific sight. Without it, it just stays horrific; also the smell factor is really important with chocolate, when you smell it a desire forms even though it is in conflict with what you see.

OM : How do you make this casts?

SjS : I make alginate molds from the bodies then cast a positive in plaster after that I make the silicone molds.

OM : how did people react on the chocolate?

SjS : most typically there is a conflict; either with the viewer or me is in conflict personally on how they should respond. That said people are positive and can appreciate the beauty of the chocolates and the contrast they represent.

OM : Were they ever exhibited in social situations – open for people to eat them?

SjS : No, But by situation when it was part of a traveling exhibition in England, I made the forms in a chocolate/wax mixture. When I got them back, there were teeth marks from people trying to eat them.

OM : what was your most important experience when you exhibited the chocolates?

SjS : the way people reacted to them. Because I found that when I told somebody about this work, without them seeing images or seeing the work the response is always the same, very negative like “what’s the point?»

I suppose I would react the same. But when you see chocolates in person – and smell them, the power of smell comes to play. Because people become very confused when they smell them, they want to eat them but they know they shouldn’t want to. Confusion sets in, then people asked me if I made these molds from my friends – I said: “No I made them in a morgue.” – “Yeah but they look like they are people!” So you can see the are fighting with the idea of what they think they see and what is actually there. The smell has an interesting effect on their perception. Because they desire them and would like to eat them, then they cant be bad like death. It was the most striking responds overall that I got on this piece.

OM : what do you think about cannibalism and its connotation in this work?

SjS : the Idea of cannibalism in this work is only peripheral. It has more to do or construed from my catholic upbringing – I grew up “eating the body and blood of Christ” every Sunday. The idea of actual cannibalism doesn’t really faze me either way. Whether it is done because people were actually hungry or because of some ritual. I am more interested in the physiological idea of the transformation of food into body; it has only superficial connections to cannibalism… but more to do with faith in something, believing the nonsensical. The conversion of food to body, this takes devotion….

OM : What were your Moscow experiences?

SjS : The morgue was very shocking place. They weren’t very organized in dealing with the bodies, or at least they had a very different approach to death. Maybe because many of the bodies were unidentified and lay there for months. Overall a quiet a desperate place.

OM : does the difference between the morgues themselves affect your work?

SjS : No, The morgue in Russia was dirty and bizarre, but the morgue I was working in USA was also very strange. It was in this abandoned university complex of buildings. And it was in the basement and all the upper floors were boarded up and the morgue classically is in the basement, and the only other thing in basement were motorcycle lessons- for riding motorcycles. Shallow irony I guess because many of the bodies in the morgue were from motorcycle accidents. They all had the same injuries. And I think there was the same bureaucratic idea of life: “will put the motorcycle lessons in the same building”. I don’t know, it was very weird. Because there was a huge complex of buildings that were all abandoned except of the morgue and motorcycles. So those kinds of things were the same in America and Russia.

OM : did people who were working in morgue know why you are there?

SjS : they knew in the both places more or less. I think at that point in the Russian morgue I didn’t know much Russian. I was there but I didn’t really understand what is going on too much between the workers. But for them I was just some guy coming to do something and later have some vodka and fish with them. They couldn’t care less; I just make their time a little more interesting

OM : How do you feel to be part of a Dead or Alive Show?

SjS : it’s a nice show. From my side I think it is appropriate, but I could fit in the other section as well. For me that’s the way the chocolates are, it’s not about people being dead, it’s about the living that eat them. A continuation….

The Disquieting Food Art of Stephen J Shanabrook

“Evisceration of waited moments,” Stephen J Shanabrook. Photo via aeroplastics.net.

Stephen J Shanabrook is a New York and Moscow-based artist who uses food both as medium and metaphor. Using commonplace materials and forms generally seen as benign indulgences— sweets, chocolate, and cotton candy — he brings about disturbing new meanings, exploring the intersections of desire, violence, permanence, and death. (See his “Waterboarding” sculptures — chocolate-waterboarded choir boy Christmas statues — that we covered last week.)

In the 1990s, Shanabrook, who spent his youth working at a chocolate factory, went to morgues in Russia and the US and made molds from the fatal wounds of anonymous people, cast dark chocolate pieces, placing them into luxury chocolate boxes. The series of works, which Shanabrook described as “very close to the edge, the forbidden place for artists,” are essentially representations of death or what one critic called “bonbons of mortality.”

“On the road to heaven the highway to hell,”

Shanabrook casts “The remnants of a suicide bomber” in dark chocolate for the sculpture “On the road to heaven the highway to hell.”

“On the road to heaven the highway to hell,”

“Morgue Chocolates,” Stephen Shanabrook. Photo via aeroplastics.net.

“Morgue Chocolates,” Stephen Shanabrook. Photo via aeroplastics.net.

“Unidentified,”

“Wedding Favors,” 2006.

“Wedding Favors,” 2006

“I Eat People, They Eat Me,” 1992

“Two Friends Sleeping,” 1990.

Shanabrook’s earlier chocolate works include “I Eat People, They Eat Me,” made from casts from teeth collected by dentists in the Netherlands and America, and “two friends sleeping,” with fetal goat cast in chocolate on top of chocolate bars.

Cotton Candy

“Bandaged”

In the 1995 piece “Bandaged,” Shanabrook used cotton candy to test the correlation between sugar, wounds, and scarring. Shanabrook writes:

“The cotton-candy machine comes from the celebrative and festive times of the formative years, the dog days of pure experience. By wrapping my hands in cotton-candy (sugar) that consequently is liquefied by the sun I propose an opening to past pure experiences. The sugar sticky syrup like blood eventually becomes crusty, a scab that forms giving way to the scar. This action searches at the points where reality exchanges with the events and ideas of the past, thus are negating the action to the point where it ceases to be relevant.”

The performance piece “Slapped in the face until your shit turns red,” was recently part of the group exhibit “Fools Food” held at the Contemporary Art Center in Neuchatel, Switzerland. Set against a stark white background the artist stood eye level with a fully running cotton candy machine fixed with fans and allowed himself to get quite literally slapped in the face with cotton candy.

Shanabrook told us his reason behind the performance:

“The cotton candy performance for me is a simple gesture to conjures up feelings of forcing ones beliefs on others… even beliefs that seem sweetly correct. This action is the interpretation of a mental torture for the unwilling recipient.”

“Slapped in the face until your shit turns red”

INTERVIEW ADDICT MAGAZINE by HEATHER STEPHENS

PRESS RELEASE. HELL & BACK / XL together with ArtStrelka Projects / Moscow / 2006

Renata Salecl*

Stephen Shanabrook’s new work of melted plastic touches two fascinating and at the same time traumatic obsessions of contemporary society: the status of celebrity and death. Shanabrook has for a while been keen observer of our society’s dealing with death, especially with the fact that the latter is more and more perceived as one of the prohibited issues today. If in the Victorian times, sex was taboo, in today’s society death is becoming one. Parents, for example, often do not allow children to attend funerals in order to protect them from the traumatic nature of death and dying. However, as we know from psychoanalysis, what is prohibited and denied often becomes more traumatic than what is allowed. Shanabrook’s work has already in the past exposed the traumatic nature of death. His new work, however, makes death part of the new type of obsession with celebrity culture. The latter have today replaced old authorities as points of people’s identification. This obsession with celebrity culture, on the one hand, creates an impression that everyone can become famous if he or she is able to sell his or her image in the right way, and, on the other hand, it has also created the perception that everyone can become attractive and eternally young, if only one works on one’s image. In this celebrity obsessed world there also seem to be no place for death and decay.

What does it mean when Stephen Shanabrook burns celebrity dolls so that the plastic they are made of melts into horrifying squashed objects. First of all, Shanabrook shows what an object of attraction can easily turn into: from a sublime, inaccessible object of admiration or desire, it can become perceived as an abject, squashed object which provokes unease and anxiety. Melted figures Shanabrook is playing with illustrate very well the Freudian nature of the uncanny – the fascinating and at the same time horrifying nature of the object of desire. But when Shanabrook mixes new celebrities like Zidane, Bruce Willis or Tupac with old mythological figures he mockingly shows how mytholigization from today does not so much differ from that in the past. Both in their own way tried to offer a solution to subject’s problems with death and desire.

* Renata Salecl is the philosopher and sociologist, one of the leading representatives of Ljubljana School of Psychoanalysis; professor at the Institute of Criminology, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

PRESS RELEASE. BEING WET / 31GRAND GALLERY / NYC /2001

on being young and thoroughly moist

as fluids leave their residue of time

the body left with corrosion

seeks a new path…… Stephen j Shanabrook

Shanabrook is most known for his morgue chocolate editions of cast wounds in a chocolate candy box motif. In his new series of work and exhibition “being wet”, the artist continues to follow his incessant struggle and poetic search of beauty from the morose. The central though indirect character of “being wet” is the bullet. For Shanabrook there is only one bullet always in the air, circling the planet. Using these ballistic adventures Shanabrook creates a kind of classic Wonderland, where changing the scales and the roles, metaphorically switching places around the table, he puts the viewer into a confrontation with the expected. ”bird’ shit, rain and landscape”, the first from the ballistic painting series. In this performance Shanabrook will work a painting throughout the evening with a paintball gun that delivers laser guided specially prepared balls of tube oil paint to a clear plastic canvas.

The audience will view the painting being made from the opposite side — “in the line of fire”. ”weather balloon” — seizing the moment of “earthly/heavenly conflict as the soul ascends”, Shanabrook’s helium balloon is shaped to support a jacket found in the street with splatters of dried blood and asphalt abrasions. ”food stains” an installation spread out before our feet on a seemingly well slept mattress while several metal goblets form a spine, topped off with a cast human brain all brought to “life” with 10 thousand volts of electricity. The above and other endeavors can be seen as part of Shanabrook’s concept of “being wet”.

_________________________________________________________________________________________